The idea that people learn differently has been around for decades, giving rise to various models and approaches to education. Learning styles—often categorized into types such as visual, auditory, and kinesthetic—suggest that individuals have preferred ways of absorbing and processing information. The question remains: do learning styles really make a difference in how effectively students learn? This article explores the concept of learning styles, their scientific foundation, and whether catering to these styles can truly enhance educational outcomes.

What Are Learning Styles?

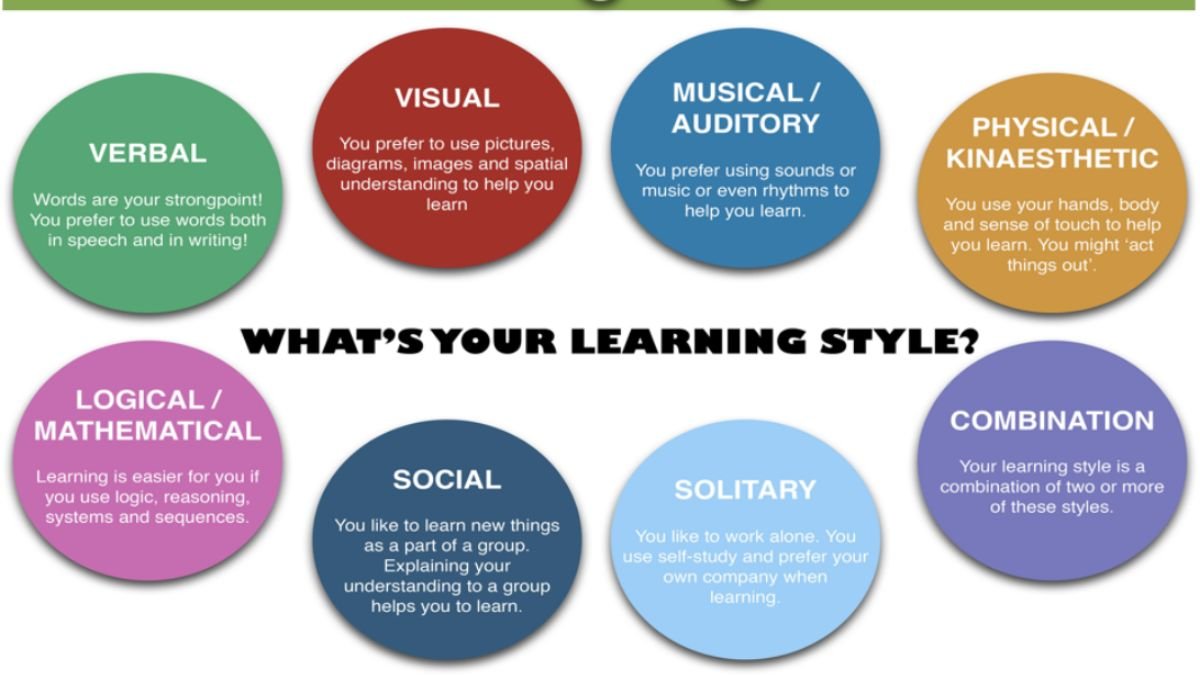

Learning styles refer to the theory that individuals have specific preferences for how they receive and process information. These preferences are said to influence the effectiveness of teaching methods. One of the most widely known models of learning styles is the VARK model, developed by Neil Fleming in 1987. VARK stands for Visual, Auditory, Reading/Writing, and Kinesthetic, representing different modalities through which people are believed to learn best.

- Visual learners prefer to see information, such as through charts, diagrams, and videos.

- Auditory learners absorb information best through listening, such as in lectures or discussions.

- Reading/Writing learners favor learning through text-based materials.

- Kinesthetic learners benefit from hands-on activities and experiential learning.

This model, along with other similar ones like Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences, has permeated educational systems around the world. Teachers are often encouraged to cater to different learning styles to meet the diverse needs of students. However, despite its popularity, the learning styles theory has faced significant criticism.

The Popularity of Learning Styles in Education

Why has the concept of learning styles gained such a strong foothold in education? One reason is that it offers a simplistic and appealing solution to the complex challenge of teaching diverse groups of students. Educators, parents, and students alike are drawn to the idea that learning can be customized to suit individual needs, potentially improving engagement and outcomes. For instance, if a student struggles to grasp a concept through reading but excels when information is presented visually, it seems logical to tailor lessons to their preferred learning style.

Moreover, many educational materials, from textbooks to online courses, promote the idea of learning styles. Teacher training programs often emphasize the importance of understanding and accommodating different learning styles. This has led to the widespread adoption of differentiated instruction, where teachers are encouraged to design lessons that appeal to a variety of learners. On the surface, this seems like a progressive approach to education. However, the scientific community has raised doubts about the validity of learning styles as an effective framework for teaching and learning.

The Science Behind Learning Styles: Do They Hold Up?

Despite their popularity, the scientific evidence supporting learning styles as a valid educational tool is weak. Numerous studies have attempted to verify the idea that individuals learn better when taught according to their preferred learning style, but the results are inconclusive at best. A 2009 comprehensive review by the Association for Psychological Science (APS) found little evidence to support the claim that matching teaching methods to learning styles improves learning outcomes.

One of the main issues with learning styles theory is that it oversimplifies the learning process. Cognitive psychologists argue that learning is far more complex than simply receiving information through a preferred sensory channel. Research suggests that regardless of one’s preferred learning style, the most effective teaching methods often involve engaging multiple senses and cognitive processes.

For example, a study published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest found that students benefit more from a combination of instructional techniques—such as visual aids, interactive discussions, and hands-on activities—rather than relying on one particular learning style. The study suggested that while students might express a preference for certain modes of learning, this does not necessarily translate into better learning outcomes.

The Problem with Learning Style Labels

Another criticism of the learning styles theory is that it can inadvertently limit students’ potential. By labeling students as “visual learners” or “auditory learners,” educators may inadvertently narrow their teaching methods, confining students to a single mode of learning. This can be particularly harmful because it ignores the reality that different tasks and subjects may require different learning strategies.

For instance, learning to play an instrument requires auditory learning, but it also involves kinesthetic elements. Similarly, solving complex math problems might benefit from visual aids, but the underlying concepts must also be processed logically and conceptually. Overemphasizing learning styles risks pigeonholing students into fixed categories, potentially hindering their ability to develop diverse and adaptable learning skills.

Furthermore, students might internalize these labels, believing that they can only learn in one specific way. A student who believes they are a “visual learner” might shy away from opportunities to develop other learning strategies, such as active listening or hands-on experimentation. This narrow approach can limit the growth of a student’s overall cognitive abilities.

A Broader Approach to Learning: Cognitive Flexibility

Rather than focusing on learning styles, modern educational research emphasizes cognitive flexibility—the ability to adapt to different learning environments and demands. Cognitive flexibility involves developing a wide range of skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and the ability to switch between different modes of learning. Instead of fitting students into predefined categories, cognitive flexibility encourages them to approach learning with an open mind, adapting their strategies based on the task at hand.

Incorporating multiple teaching methods—such as visual aids, auditory discussions, reading assignments, and hands-on projects—encourages this kind of flexibility. This approach allows students to engage with material in various ways, strengthening their overall learning capacity. For example, when teaching a history lesson, educators might combine text readings with documentary footage, group discussions, and role-playing activities. This not only caters to different learning preferences but also enhances students’ ability to learn through multiple channels.

The Role of Metacognition in Learning

Another critical factor in effective learning is metacognition—the ability to think about one’s own thinking processes. Metacognition involves self-awareness about how one learns and the ability to adjust strategies accordingly. When students develop strong metacognitive skills, they can identify which learning strategies work best for them in different contexts, rather than relying on a fixed learning style.

For instance, a student studying for a biology exam might realize that while reading the textbook helps them understand theoretical concepts, they retain information better when they draw diagrams or discuss the material with peers. By reflecting on their learning process and adapting accordingly, students can become more effective learners, regardless of their supposed learning style.

A Balanced Approach: Differentiation without Over-Reliance on Styles

While the evidence against learning styles is strong, it does not mean that teachers should entirely disregard individual differences in how students learn. Students do have preferences, and acknowledging these can improve engagement and motivation. However, educators should avoid rigidly adhering to the idea that students can only learn in one particular way. Instead, teachers should strive to provide a diverse range of instructional methods that cater to various cognitive processes, fostering a well-rounded and adaptable approach to learning.

Differentiation in the classroom can still play a valuable role, but it should be based on a broader understanding of how learning works. Rather than narrowly focusing on learning styles, teachers can use assessments, observation, and feedback to understand how students interact with material. This approach allows for flexibility and innovation in teaching methods, while still considering the unique needs of each student.

Conclusion: Learning Styles and Their Place in Education

So, do learning styles really make a difference? The answer is more complex than a simple yes or no. While learning preferences exist and may influence how students engage with material, the evidence does not support the idea that teaching to specific learning styles leads to better educational outcomes. Instead, research suggests that a more holistic approach—one that encourages cognitive flexibility, metacognition, and the use of diverse teaching methods—is more effective in fostering meaningful learning.

Ultimately, education is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. While learning styles offer an intuitive way to think about how students learn, they should not be the sole basis for instructional decisions. By embracing a broader, more flexible approach to teaching, educators can help students develop the skills they need to succeed in an ever-changing world of knowledge and information.